To start with most of the organizations that deal with customer data think that they are doing enough and more to protect their client’s data and have taken all the measures that are needed to safeguard the interests of all the stake holders. They think DPDPA is all about putting the documentation in order, to prove that what they are doing is all what is needed.

But most often it’s the other way around. The devil is in the details, and more so if one tries to get into the details systematically.

Let’s use an example to understand this, by taking a case of a fictitious Quick Commerce company.

It has customer base all over the country and delas with multiple vendors. So, they have to mange the data of both clients and vendors.

They believe that they are DPDPA compliant because

- They have published their privacy policy on the website.

- They made their customers agree to their terms of services.

- All their applications run behind a fire wall.

- Al the data transmission happens over secure networks (SSL/https).

- The data at store is encrypted.

Now let us look at what is the ground reality. They perform their DPDPA readiness audit and are shocked by what they find.

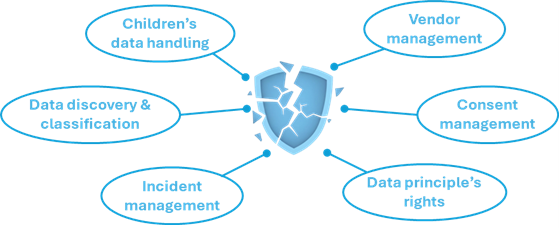

Data discovery & classification

In my previous blog we talked about classification of data. And going by that definition, the company holds all categories of data – Personal, Sensitive, Children’s and non-sensitive.

From the exercise of data discovery, what quickly emerged was that this data was widely dispersed across the organisation. It existed in databases, image repositories, PDF files, email systems, backups, and data exports shared with vendor applications. Ownership of these different data stores was spread across multiple teams, each managing their own systems in isolation.

As a result, no single team had a complete view of where a specific customer’s data resided or how long it was being retained. There were also no clear answers to fundamental questions such as whether the data was protected in line with its classification, whether principles of data minimization were being followed, or whether the data was being deleted once it was no longer required.

Compounding this challenge was the absence of any mapping between customer data and the applications or locations in which it was stored or processed. Without this visibility, managing data responsibly—and demonstrating compliance—became increasingly difficult.

Consent management

Consent was obtained only once, at the time of onboarding, and treated as just another data point alongside other customer information. It was captured as a broad, generic consent, without clearly articulating the specific purposes for which different types of data were being collected or used.

Additionally, there was no versioning of consent. Customers who onboarded at different points in time may have agreed to different versions of the terms, but the organization had no practical way to distinguish which version of the consent applied to which customer—even though terms and privacy notices evolve over time.

Consent withdrawal was also not supported through any automated mechanism. Requests to withdraw consent were handled manually through email exchanges, making the process slow, operationally intensive, and difficult to track consistently.

Children’s data handling

In the case of minors who were onboarded onto the platform, age verification was not part of the registration journey. As a result, the organization had limited visibility into whether the user was a minor at the time of onboarding.

Even in instances where users indicated that they were underage, there was no structured process to seek and record verifiable consent from parents or legal guardians.

Data principal’s rights

When a data principal (the customer, in this case) requested deletion of their data, the request was managed through email exchanges and typically took three to four weeks to complete. No audit trail was maintained for these requests.

There was no system-level enforcement to ensure that the data was deleted across all systems where it resided.

A similar challenge arose when customers requested information on what personal or sensitive data was being processed and for what purposes. There was no centralized mechanism to provide this information, requiring coordination with multiple application owners and external vendors. This process was time-consuming, operationally inefficient, and placed significant strain on internal teams.

Vendor management

There were no mechanisms in place to conduct periodic vendor compliance assessments. Aadhaar images collected for KYC purposes were retained indefinitely, with no provision for deletion even after the vendor was disengaged from the system.

In addition, analytics data shared with external partners contained raw personal identifiers.

Incident management

To assess the effectiveness of their incident management workflow, the organization tested a common scenario in which a customer requested the deletion of all personal data.

While the application team removed the customer’s profile, the customer’s data continued to exist in the CRM system, and related call centre recordings were still retained. Additionally, the third-party KYC vendor continued to store the customer’s Aadhaar details.

This exercise revealed that data deletion was being handled as a series of isolated actions rather than as a coordinated, end-to-end process.

Conclusion

This organization was not negligent. It had invested in security, policies, and infrastructure. Yet, it fell short because DPDPA compliance is not about intent or documentation—it is about operational reality.

Now Coming back to real life, even major players such as Star Health Insurance and Policy bazaar have experienced large-scale data exposures, where millions of customer records were leaked due to security and privacy gaps. These incidents reflect weaknesses that go beyond infrastructure — such as lack of data mapping, incomplete consent or retention practices, and inadequate breach response — all of which the DPDPA is designed to address.

Building on the above example, and in conjunction with the blog recently written by my colleague Manoj Sinha – “5 Reasons Why DPDPA Could Apply to My Company”—it becomes evident that most organisations, in their current mode of operation, are likely to fall well short of DPDPA compliance.

Organisations must now take a hard look at how customer data is managed and put in place the governance, systems, and processes required to meet DPDPA obligations.